It’s great entertainment watching TV. If you have cable, then that’s even better. Now, with streaming services right on your phone, you can never miss an episode or live broadcast. But it was never this; TV had only a few stations, depending on where you were and how strong your signal was —or, should I say, your antenna.

Television didn’t arrive overnight. It was stitched together from dozens of inventions, business bets, and a steady stream of “what if?” moments—from spinning disks and vacuum tubes to satellites, cable headends, and, finally, apps on our phones. Here’s the story, in plain English.

To understand a culture, look at its television. Not because TV is perfect or pure—it’s neither—but because it’s where technology, storytelling, business, and our daily rituals meet. From rabbit ears to recommendation engines, TV has kept reinventing itself while still doing the same old magic trick: putting a shared story between you and the rest of the world.

In this blog, we will go through the history of the invention that has shaped us all. That has helped us find our purpose and launch many careers. Whether you wanted to be an MTV VJ, actress or actor, singer, fashion designer, athlete, news anchor, reality TV star, or journalist, television has shaped us in many ways. Without it, our lives would be a lot less entertaining.

How TV Came About (the invention era)

Television began with curiosity and experimentation, paving the way for the first moving images.

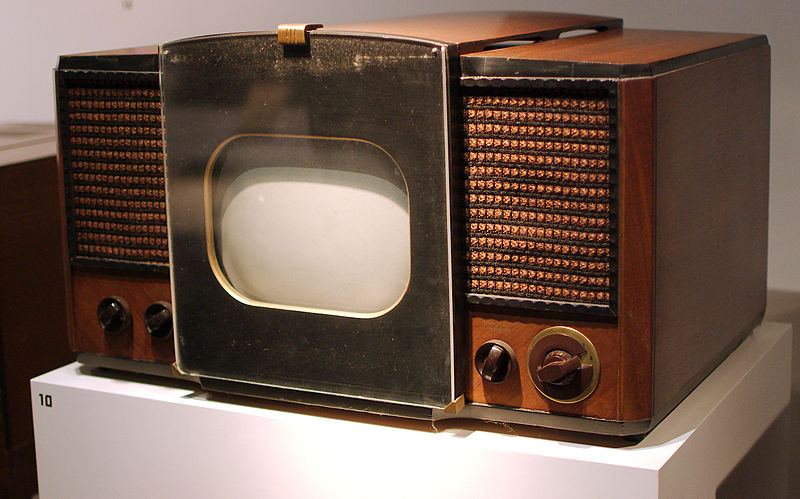

The earliest TV wasn’t electronic at all. In 1884, Paul Nipkow patented a rotating “Nipkow disk” that scanned images line by line. In the 1920s, inventors like John Logie Baird (UK) and Charles Francis Jenkins (US) demonstrated grainy, mechanical television—silhouettes and moving outlines more than shows.

All-electronic TV (1920s–1930s).

The key breakthrough was electronic scanning. In 1927, Philo T. Farnsworth transmitted the first all-electronic TV image. At RCA, Vladimir Zworykin developed essential camera tube technology (the iconoscope). After patent disputes, the industry settled on electronic TV as the future.

The first broadcasts.

RCA used the 1939 New York World’s Fair to unveil TV to the American public; President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s opening address was telecast. In 1941, the FCC authorized commercial TV in the US, and New York’s WNBT (now WNBC) and WCBW (now WCBS) began regular, advertiser-supported programming.

How TV Evolved (standards, color, and growth)

Postwar boom and the FCC “freeze.”

World War II paused mass production. By 1948, TV exploded—so fast that the FCC (Federal Communications Commission, the government agency regulating communications) froze new station licenses (1948–1952). This was to sort out interference and channel assignments. The Sixth Report and Order (a formal FCC policy decision in 1952) created a nationwide plan and opened up UHF (Ultra High Frequency) channels. This paved the way for many more local stations.

Color and the NTSC standard.

After early, incompatible color attempts, the US adopted the NTSC (National Television System Committee) color standard in 1953. It was crucially compatible with black-and-white sets. RCA and NBC pushed color in the late 1950s and 1960s. By the late ’60s, color was the default.

The Big Idea: networks and affiliates.

A network supplies programs. Local stations carry them. This model lets national advertisers reach the whole country while preserving local news and identity.

The “Basic Stations”: How the Big Networks Started

- NBC (National Broadcasting Company) – Created by RCA (originally a radio network in the 1920s under David Sarnoff’s leadership). Its TV network launched commercially in 1941 and became a color pioneer in the ’50s–’60s.

- CBS (Columbia Broadcasting System) – Built by William S. Paley, who turned a small radio network into NBC’s chief rival. CBS Television began regular commercial service in 1941 and dominated with news and prestige dramas.

- ABC (American Broadcasting Company) – Born when the FCC forced NBC to divest its “Blue Network.” The Blue was sold (1943) to Edward J. Noble and later merged with United Paramount Theatres, where Leonard Goldenson led its TV expansion. ABC’s TV network ramped up in 1948.

- DuMont Television Network – Founded by TV set and tube innovator Allen B. DuMont. A technical trailblazer (1946–1956), it couldn’t match the others financially but helped seed major stations.

- Fox – A later entrant (1986), launched by Rupert Murdoch after acquiring Metromedia stations. With “The Simpsons,” NFL rights, and edgy primetime, Fox turned the “Big Three” into the “Big Four.”

- Public Broadcasting (PBS) – The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting; PBS was formed in 1970 to distribute educational and cultural programming to member stations, succeeding NET.

(Two other milestones worth noting: the All-Channel Receiver Act (1962), which required UHF (Ultra High Frequency) tuners in all sets—boosting smaller stations—and the US switch to digital TV (ATSC, Advanced Television Systems Committee standard) completed in 2009.)

How Cable TV Came About (and why it mattered)

Community antennas (late 1940s).

Early cable—then called CATV for “community antenna television”—was a clever hack. In hilly towns, broadcast signals were weak. Entrepreneurs hoisted big antennas on mountaintops, captured distant stations, and ran coaxial cables (wires designed to transmit TV signals with low loss) down to homes. Pioneers like John Walson, L.E. Parsons, and Robert Tarlton are often credited with those first systems.

From signal-helper to channel-creator (1970s).

The turning point was satellite delivery. In 1972, HBO launched as a paid channel. In 1975, it beamed a major live event via satellite to cable systems. This proved cable could carry exclusive content nationwide. In 1976, Ted Turner launched his Atlanta station, WTBS. It became the first “superstation,” turning a local UHF outlet into a national basic cable channel. Shortly after came niche networks: ESPN (1979), CNN (1980), MTV (1981), Discovery (1985), and many more.

Deregulation and the big bundle (1980s–1990s).

Policy shifts—notably the 1984 and 1992 cable acts—and satellite distribution fueled growth. Cable stitched dozens, then hundreds, of channels into a bundle. It paired must-have networks with smaller ones. They were supported with advertising and subscription fees. Later, digital cable (a method using digital signals for better quality and more channels) added more capacity and on-demand menus.

The internet era begins (2000s).

Broadband, better video compression, and cheap storage laid the groundwork. YouTube (2005) normalized short-form online video; Netflix moved from DVDs to streaming in 2007. Devices like Roku (2008), game consoles, and smart TVs brought apps to the living room. In 2013, Netflix’s House of Cards showed that internet distributors could make hit originals.

Cord-cutting and “live, but online.”

As on-demand libraries grew, some viewers ditched the cable bundle. This was called “cord-cutting.” To keep live channels accessible without cable, new services—so-called vMVPDs—stream channel lineups over the internet: Sling TV, YouTube TV, Hulu + Live TV, and others. Meanwhile, major studios launched their own services (Disney+, Max, Paramount+, Peacock). They pulled shows back from third-party platforms.

FAST and free options.

Alongside subscriptions, FAST (Free Ad-Supported Streaming TV) platforms like Pluto TV and Tubi created 24/7 “channels.” They use themed, continuous streams—no login, just ads. This re-creates a lean-back (relaxed, passive viewing), TV-like feel in an app.

Today’s landscape.

- On-demand streaming: pick any episode, any time.

- Live streaming: watch news, sports, and local stations through internet bundles.

- Hybrid models: ad-free tiers, cheaper ad-supported tiers, and free FAST options.

- Re-bundling: companies now bundle multiple services together (or with wireless/internet) to simplify costs—echoing the old cable bundle, but app-based.

The Rise (and Responsibility) of the Algorithm

Back in the day, the TV guide was a grid. Now it’s a guess. Platforms lean on algorithms to suggest what you might like next. They try to balance accuracy with discovery. When it works, it feels like a friend who “gets” you. When it doesn’t, the interface is a maze: five services, eight profiles, 30 minutes of scrolling—and somehow you’re rewatching the same comfort show.

Curation matters. Human-made collections, editorial spotlights, and “if you liked X, try Y” rails can break us out of bubbles. Viewers can help themselves by mixing “known-good” viewing with a little wild-card energy. Try an international drama, sports doc, or short-format anthology. The algorithm learns. Your taste grows.

Bingeing, Breathing, and the Pace of Story

Binge releases changed how stories flow. Writers can build momentum across episodes without pausing for a week’s worth of anticipation. Clues pay off faster; arcs feel more novel-like. But something was lost too: the shared pause that lets theories bloom and characters breathe in the cultural air.

It’s no accident that some series are now released in batches or weekly again. The cadence of release is part of the storytelling. A weekly drop can turn a show into a conversation that lasts months, while a binge can make the same show feel like a fever dream you wake from in a weekend. Neither is “right”—they’re different instruments, and smart creators choose their tempo.

Global Stories, Local Screens

Subtitles and dubs used to be a niche; now they’re normal. A thriller from Seoul, a telenovela from Bogotá, a cozy mystery from Copenhagen—global hits prove that specificity travels. Audiences will read, listen, and adapt if the characters are compelling and the world feels lived in.

This global exchange has reshaped how shows are made. Co-productions and international writers’ rooms combine regional authenticity with universal stakes. The result: richer worlds, new archetypes, and an industry less dominated by a single cultural center.

Representation Isn’t a Trend—It’s Craft

When TV broadens who gets to be the hero, the show gets better. It’s not just about checkboxes; it’s about texture, humor, history, and conflict that feel true. Representation behind the camera matters just as much. Diverse writers, directors, editors, and showrunners bring choices to the screen that can’t be faked—how a joke lands, how a home looks, which silences are charged.

The payoff is measurable in audience loyalty and in the kind of “I see myself” moments that turn casual viewers into evangelists. And yes, representation includes age, disability, class, region, and faith—not only what we most often talk about online.

Live Is the Last Campfire

Sports, award shows, reality finales, breaking news: live programming remains the place where TV behaves like a public square. Even as social media fragments attention, a true live moment can still pull us into the same emotional room. That’s why leagues negotiate immense rights deals and platforms build their entire tech stack to keep live streams stable at scale.

Live also reveals the human side of television—the flubs, the pauses, the unexpected. In a world of pristine, polished content, those rough edges make the experience feel alive.

The Business Model Is the Plot Twist

Television economics used to be simple: ads fund shows; cable bundles fund channels. Now it’s a three-way negotiation among subscriptions, advertising, and data. We’ve seen ad-free tiers, ad-light tiers, and the return of free, ad-supported “FAST” channels that feel like classic TV with a modern guide.

The net effect for viewers is a bundle you manage yourself—passwords, profiles, and monthly choices that add up. The winners will be services that respect time and money: clear value, fewer hoops, and the confidence that a show you start will actually finish its run.

TV and the Second Screen

No one just watches TV anymore. We chat, scroll, meme, and look up the actor we’re sure we’ve seen somewhere else. This second-screen life can enrich a show with context and community—or it can puncture the spell. Smart productions anticipate this: official podcasts, behind-the-scenes content, companion explainer videos, and tasteful on-screen recaps meet the audience where they already are.

For viewers, a simple practice helps: pick your mode. If it’s a meticulous drama, put the phone face down for an hour. If it’s comfort TV, lean into the scroll. Treating attention as a dial, not a switch, makes the experience feel intentional instead of scattered.

What’s Next: Interactivity, Personalization, and Presence

A few near-future threads to watch:

- Interactivity (where it makes sense): Not choose-your-own-adventure gimmicks so much as small, meaningful choices—alternate angles for sports, character-focused recaps, spoiler-safe previews.

- Taste profiles you can steer: Sliders for “surprise me vs. play it safe,” “light vs. heavy,” or “30-minute vs. 60-minute” could make recommendations feel less opaque.

- Ambient screens: TVs are becoming information hubs—art, dashboards, ambient displays—blending with smart homes in ways that make the “off” state feel purposeful.

- Accessibility by design: Better captioning, descriptive audio, customizable UI contrast and font sizes—features that help many, not just a few.

How to Watch Well

If TV is a diet, balance matters. A practical recipe:

- Keep a “Now Watching” list of 2–3 active shows to cut down on endless browsing.

- Add one “stretch” slot for something outside your usual genre each month.

- Use the first-episode rule: you don’t have to finish everything. Sample, then commit.

- Watch one big thing live each season—sports final, awards night, or a cultural event—just to remember how fun the campfire can be.

Quick Timeline

- 1884–1920s: Mechanical TV experiments (Nipkow, Baird, Jenkins)

- 1927: Farnsworth’s first all-electronic image

- 1939–1941: RCA/NBC demos; US commercial TV begins

- 1948–1952: FCC license “freeze”; spectrum plan expands TV

- 1953: NTSC color standard adopted in the US

- 1962: All-Channel Receiver Act boosts UHF stations

- 1967–1970: Public Broadcasting Act; PBS forms

- 1972–1976: HBO launches; satellite delivery; WTBS becomes the first superstation

- Late 70s–’80s: ESPN, CNN, MTV, and the cable boom

- 2007–2013: Netflix streaming; premium streaming originals

- 2015–present: Live TV over the internet (vMVPDs), studio streamers, and FAST

Final Thougths:

If you want to understand a culture, look at its television. TV is not perfect or pure—it’s neither. But it’s where technology, storytelling, business, and daily rituals meet. From rabbit ears to recommendation engines, TV has kept reinventing itself. It still does the same old magic trick: putting a shared story between you and the rest of the world.

Television is still a communal art form, even when we watch alone. We quote it at work, build friendships around it, and use it to mark time in our lives. The screens got sharper, the libraries got deeper, and the paths into a show multiplied—but the core exchange didn’t change: “Let me show you something,” the screen says. “Let me feel something with other people,” we answer.

And when it’s good, it feels like both promises are kept.

This was good insight on Television, it was also a nice stroll down memory lane reading about how much television and the way we watch it has changed over the years.

LikeLike