It’s that Day of the year again—you know, the one where everyone suddenly becomes a publicist for their relationship. Social feeds turn into highlight reels, captions get suspiciously poetic, and even people in shaky situations go out of their way to prove everything’s “perfect.” Cue the overpriced roses that’ll be half-dead by Tuesday, candy you could’ve bought last weekend for cheaper, and restaurants making bank like it’s a holiday invented specifically to stress-test your wallet. It’s Valentine’s Day—February 14—equal parts romance and performance.

And somehow, it hits everyone differently. For some, it’s a sweet excuse to slow down and feel chosen. For others, it’s a loud reminder of what’s missing, what’s complicated, or what’s barely holding together behind the scenes. Because here’s the thing: Valentine’s Day isn’t just about love—it’s about being seen. It’s about the pressure to have a story worth posting, a gesture worth photographing, a person worth tagging. And whether you’re floating on cloud nine or bracing for impact, the Day has a way of pulling back the curtain and asking one uncomfortable question: are you celebrating something real… or just trying not to look like you’re not… or are you lonely and trying to convince others you’re happy being alone…?

Valentine’s Day can feel like it was invented by a marketing team with a glitter budget, but its roots are older—and a lot messier—than heart-shaped candy displays. February 14 started as a Christian feast day honoring a martyr named Valentine. Still, the historical record is murky enough that there were multiple early saints named Valentine/Valentinus, and it’s hard to pin the holiday to a single, clean biography. The romance angle appears later: medieval culture and writers (often crediting Geoffrey Chaucer) begin linking “St. Valentine’s Day” to courtship and choosing a mate, which helps push the Day toward love rather than liturgy.

The Valentine’s Day we recognize now—cards, verses, mass participation—takes off when technology and commerce make it easy. Cheaper printing turns valentines into a product instead of a one-off handmade note, and postal changes (especially Britain’s Uniform Penny Post in 1840) make sending them affordable and routine, fueling a market for mass-produced cards. From there, the modern add-ons—flowers, candy, and the whole seasonal retail machine—are essentially later layers atop that earlier religious and medieval foundation. In this blog, we will learn about the holiday’s history and how it’s evolving. So get your wallets ready and be prepared to spend all your cash to convince the world that you’re crazy in love and happy to be…..

The Origins: Before It Was “Valentine’s”

A winter festival with a wild side

Long before Valentine’s Day was associated with romance, mid-February in ancient Rome was marked by Lupercalia, a festival held around February 13–15. Lupercalia was associated with fertility, purification, and the arrival of spring. It involved rituals that bear little resemblance to modern “date night”—more about symbolism, tradition, and societal renewal than sweet love notes. While it’s often mentioned alongside Valentine’s Day, it’s worth noting that historians debate how directly Lupercalia “became” Valentine’s Day. What’s clearer is this: mid-February already carried cultural meaning, and later traditions layered new stories and values on top.

The mysterious “Saint Valentine.”

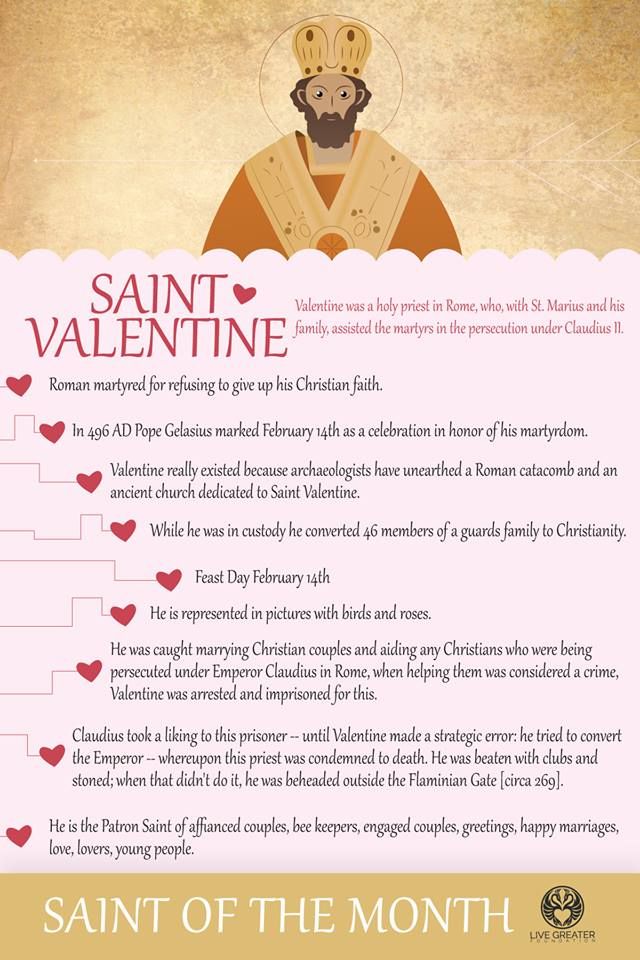

The “Valentine” in Valentine’s Day likely refers to one or more Christian martyrs named Valentinus. The problem is: the historical record is messy. Several legends exist, and it’s possible that multiple figures were combined into a single romanticized story over time. The most popular legend says Valentine was a priest who performed secret marriages against an emperor’s orders, then was imprisoned and executed. Another version says he helped Christians escape Roman prisons. Some stories include the first “Valentine” message, signed “from your Valentine”, supposedly written from jail. Whether or not those details are literal history, the themes stuck: devotion, sacrifice, and love under pressure.

The Church sets a date.

By the late 5th century, Pope Gelasius I is often credited with formalizing February 14 as St. Valentine’s Day, though the exact motivations and connections to existing festivals aren’t perfectly documented. What matters is that the Day moved into the Christian calendar, giving it a lasting place in European tradition.

The Middle Ages: When Romance Takes the Mic

Courtly love and poetic tradition

Valentine’s Day didn’t become a romantic holiday overnight. One big turning point came in the Middle Ages, especially through the culture of courtly love—a stylized, poetic form of romance associated with knights, nobles, and elaborate devotion. Writers helped cement the association between Valentine’s Day and love. Geoffrey Chaucer is often credited with linking the Day to romance in his poetry, and once the idea caught on, it spread through literature and social customs.

Early valentines: handwritten and heartfelt

By the late medieval and early modern periods, people began exchanging handwritten notes. These weren’t mass-produced or commercial—they were personal and often poetic. It was less “buy the biggest bouquet” and more “prove you can write.”

The 1800s–1900s: Love Goes Mass Market

The printing press changes everything.

In the 19th century, advances in printing and lower postage rates turned private expressions into a booming industry. Pre-made cards became widely available, making it easier for people to participate—even if they weren’t poets.

This era helped standardize the aesthetic we now recognize:

- hearts

- lace patterns

- cupids

- flowers

- sentimental phrases

The rise of modern Valentine’s Day

By the 20th century, Valentine’s Day had fully become a mainstream holiday in the U.S. and beyond, fueled by:

- greeting card companies

- candy makers

- florists

- restaurants

- jewelry marketing

It became both a cultural tradition and a commercial event—something people celebrated because they wanted to, and also because the world constantly reminded them it was coming.

Valentine’s Day Today: Romance, Pressure, and Redefinition

Modern Valentine’s Day is complicated—in a very human way.

On one hand, it’s sweet: a socially accepted excuse to be tender, intentional, and expressive.

On the other hand, it can feel like:

- pressure to perform romance

- a spending contest

- a reminder of loneliness

- a holiday that assumes everyone is coupled up

That tension is also why the holiday continues to evolve. People are reshaping it to fit their realities: celebrating friendships, self-love, long-distance love, queer love, and nontraditional relationships. “Galentine’s” gatherings, anti-Valentine’s parties, and self-care nights aren’t rejections of love—they’re expansions of what love can look like.

The Future of Valentine’s Day: Where It’s Headed Next

If the past is any indication, Valentine’s Day adapts to culture. Here’s how it’s likely to evolve in the coming years.

1) Less “one-size-fits-all” romance

The future Valentine’s Day probably won’t revolve around one narrow script (man buys flowers, couple goes to dinner). Instead, it’ll be more inclusive and personalized:

- friends celebrating friends

- partners choosing experiences over gifts

- families making it a day of appreciation

- communities turning it into a “love in all forms” holiday

2) Experience > stuff

As people become more minimalist—or more budget-conscious—Valentine’s spending may shift from objects to memories:

- cooking together at home

- weekend micro-trips

- concert nights

- personalized playlists and digital scrapbooks

- shared classes (dance, pottery, painting)

3) AI, digital intimacy, and new love languages

Technology is already rewriting romance. In the future, we’ll likely see:

- AI-assisted love letters and poems (still personal—just easier to craft)

- augmented reality cards and interactive memories

- long-distance couples using shared virtual “dates.”

- smarter gift recommendations that prioritize meaning, not just price

This doesn’t have to make romance less authentic. Tools don’t replace emotions—they change how we express them. The key will be intent: thoughtful words are still thoughtful, even if technology helps you shape them.

4) Ethical and sustainable Valentine’s Day

More consumers are paying attention to where products come from. Expect growth in:

- locally sourced flowers

- sustainable packaging

- ethically produced chocolate

- thrifted or handmade gifts

- “no-waste” celebrations

The “future classic” Valentine’s gift might be made of less plastic and more personal touches.

5) A stronger mental-health awareness angle

Valentine’s Day can stir up grief, heartbreak, anxiety, and loneliness. Future celebrations may normalize:

- kindness campaigns

- community events

- self-compassion messaging

- “You matter” style support culture.

A holiday about love can include people who are hurting as well.

So What Will Valentine’s Day Become?

Valentine’s Day began as a seasonal ritual, became associated with sainthood and legend, was transformed through poetry into romance, and, later, through industry, expanded into a global tradition.

Its future will likely be a blend of:

- more inclusive definitions of love

- more personalized celebrations

- more experience-driven choices

- more technology in expression

- more sustainability and emotional awareness

In other words, Valentine’s Day will continue to reflect the world that celebrates it.

Final Thoughts:

Honestly, that’s kind of perfect: a holiday about love has a history that’s messy, layered, and not the type of thing you can wrap up in one neat little origin story. And when you strip away the roses and the cards, that’s the real point anyway. Valentine’s Day is basically a spotlight on a simple human need—to be seen, chosen, and cherished. The traditions change, the aesthetics evolve, the price tags get wilder, but that need stays the same. If you tell me the vibe you want for your blog—fun and light, more historical/academic, or modern and story-like—I can shape the tone and tighten the length for your audience.